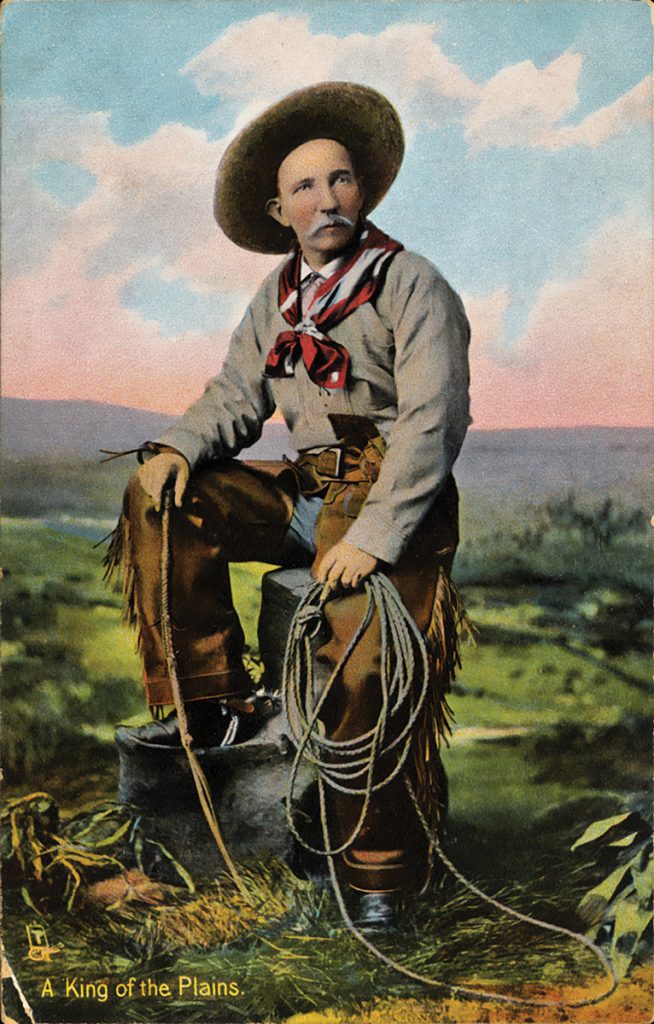

Few images in the world are as iconic as the American cowboy. This cultural archetype has captured the imaginations of songwriters, painters, poets and filmmakers for the past 150 years. It’s hard to find any place on the planet where people don’t know about the American cowboy and his trusty horse. The history of the cowboy is closely tied to the history of the Western United States. Cowboys are not just a part of Western history—they embody it.

Spanish Origins

The story of the cowboy begins in the cow country of northern Spain, more than 1,000 years ago. During the Middle Ages, Spaniards raised livestock in small bands on limited pieces of land. But around 1,000 CE, the practice of keeping cattle in large herds and grazing them on hundreds of acres took hold. The northern section of Spain was the most habitable for cattle, with miles of rich pasture and a temperate climate. This part of the country became the birthplace for several native Spanish cattle breeds that were used for milk, meat, and as work animals.

Managing large groups of cattle could only be done efficiently on horseback, so Spanish riders used horses to round up the cattle, brand them, doctor them and sort them. The techniques still practiced on cattle ranches throughout the world originated with these Spanish vaqueros, who knew how to read cattle, and rode horses bred for their ability to work livestock.

The New World

When the Spaniards came to the New World, they brought these horses and cattle with them. They also brought their expertise in working with both animals. As Spanish explorers moved up from South America into Central America and eventually the American Southwest, they brought the vaquero cattle culture with them.

Each region conquered by the Spaniards developed its own unique ranching traditions, based on the original vaquero ways. In Argentina, Brazil and Uruguay, cattle handlers were called guachos, and managed large herds of Spanish-bred cattle on the grassy Pampas regions where vast herds were grazed. In central Mexico, the cattle handlers were called charros, and became well known for their skills in roping.

The vaquero tradition soon spread to northern Mexico, and in 1598, 4,000 head of cattle were brought to the Southwest, into what is now New Mexico, and cattle were soon being grazed in the areas now known as Arizona and Texas. In 1769, a large number of cattle were brought from Mexico to California, and became part of the California Missions.

Along with the herds of cattle came the vaqueros, who not only knew how to handle cows, they were also expert horse trainers. Usually from the lower socioeconomic levels, these vaqueros were typically of mixed Spanish and indigenous blood, Spanish and African blood, or Native American ancestry. They were considered independent and nomadic, performing work for hire when needed by haciendas with large herds of cattle throughout the Southwest.

The West

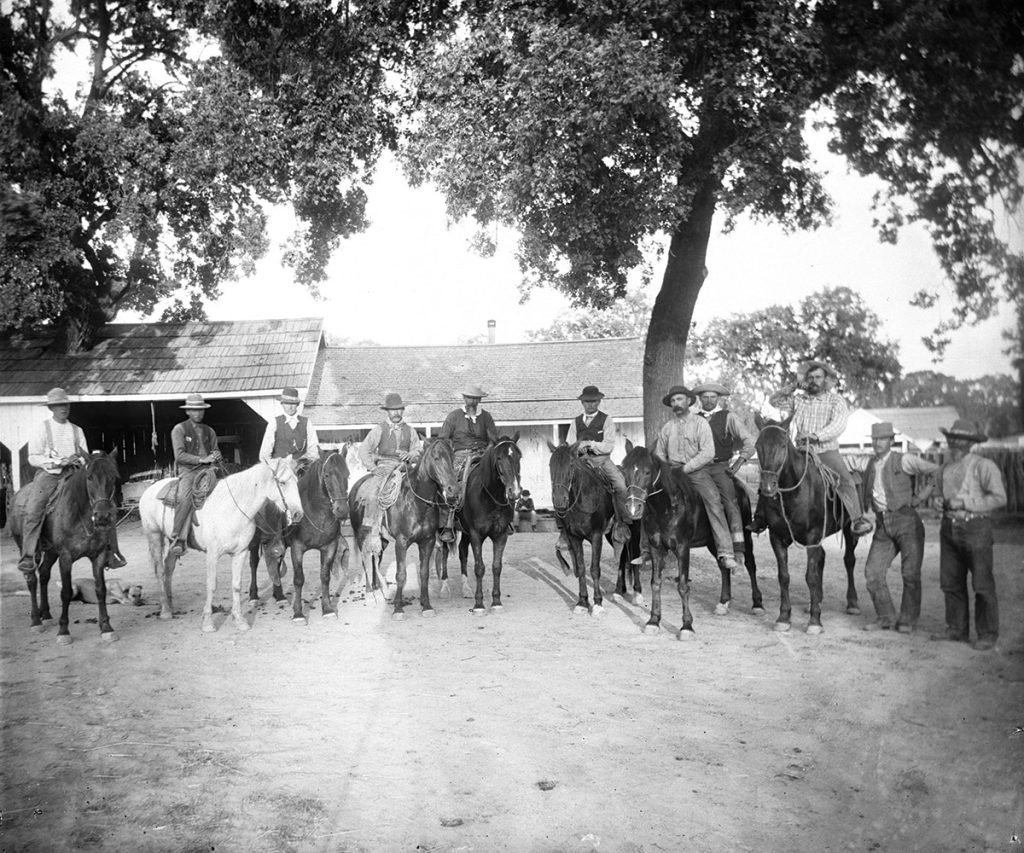

By the 1800s, cattle ranching had firmly taken hold in the American West. During the Open Range period of 1866 to 1890, cattle were allowed to roam freely, crossing thousands of acres of government land in their quest for grass. Five million cattle ranged during this period, grazing their way through Kansas, Nebraska, North and South Dakota, Montana, Wyoming and other Western states. Ranchers kept track of their animals with hot brands, which were applied to calves by these American vaqueros—now known as cowboys—who were skilled with a lasso. When cattle needed to be rounded up for branding or castration, cowboys and their well-trained cowponies did all the work of sorting and restraining the calves.

“The cowboys themselves were a diverse group of men looking for gainful employment,” says David Davis, Chief Curatorial Officer for the National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum in Oklahoma City, Okla. “At around $30 per month, a cowboy had to endure many hardships and physical dangers along the trail. Their main job was the move that herd and keep them together.”

When it was time to take steers to market, it was these same cowhands who drove the animals for weeks on end, taking them through miles of rugged terrain and dangerous territory to stockyards in Fort Worth, Texas, or Chicago, Ill.

Texas was home to many cattle ranches, and before the Civil War, many Texas cowboys were actually enslaved people—African Americans belonging to coastal prairie cattle ranches in the state. After Emancipation, many of these Black cowboys went on to work for ranches throughout the West, tending cattle and breaking horses to ride. Even more formerly enslaved people came out West looking for work.

“After the end of the Civil War, many men traveled West looking for a new start and sometimes, for previously enslaved African Americans, to escape the dangers of racism,” says Davis. “In fact, many of the working cowboys employed for cattle drives during this time were Black.”

The Open Range period came to an end shortly after the disastrous winter of 1886-1887, when cattle that had been living on overgrazed land had to endure a particularly harsh winter. Millions died, and many ranchers were forced to declare bankruptcy. Just before this period, barbed wire fence had been invented, and was discovered to be a cost-efficient way to keep cattle confined. It was also the beginning of the end for the nomadic cowboy lifestyle, since cattle fenced in with barbed wire did not require cowhands for rounding up and branding.

“During the 1880s, cattle drives began to diminish and were mostly stopped by 1890,” says Davis. “The use of barbed wire was certainly one of the factors in this decline, and perhaps one of the most important. The use of barbed wire implies the privatization of land and the end of open ranges for cattle herds, as herd owners acquired their own grazing lands and fenced them off with barbed wire. Early on in the development of barbed wire, different styles often indicated the identity of the landowner, much like cattle brands.”

Around this same time, the first livestock train car was patented, and it became easier to ship cattle to the stockyards by train, eliminating the need for long cattle drives.

“The established railroad routes in Texas offered an alternative route to markets in the east,” says Davis. “And growing cattle herds to the north in Wyoming and Montana spelled the end of the famous and romantic era of the open cattle drives.”

When the Open Range period ended, the Fence Cutting Wars ensued. The result of the fencing of public land by cattle ranchers, who were hoping to keep newcomers from grazing their cattle on these sections of land, the Fence Cutting Wars involved gangs of cowboys cutting barbed wire to open up fenced-in sections. States throughout the West were subjected to the hostilities between ranchers that erupted because of this practice. In Texas in particular, armed conflicts over fencing were not uncommon. Many of the men who had worked as cowhands were now employed as organized fence cutters.

Legislation eventually put an end to the Fence Cutting Wars. It also spelled the end of the cowboy lifestyle, the essence of which was riding with cattle on the open range.

The Cowgirl

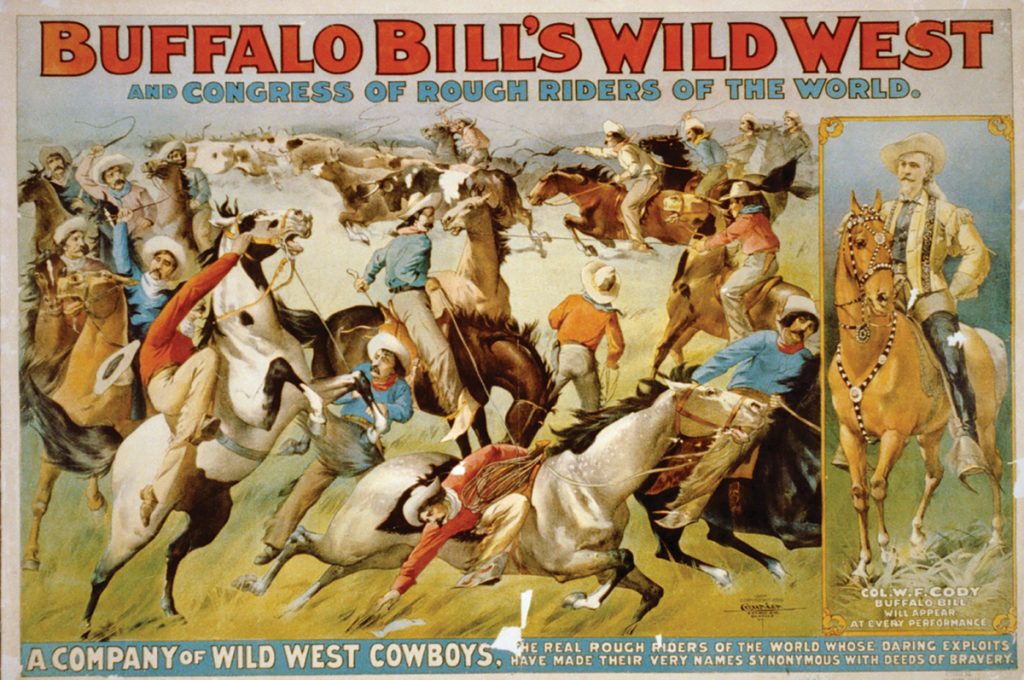

The cowboys of the 1800s are well documented, but little was written about their female counterparts. Women undoubtedly helped run ranches, and some accompanied men on long cattle drives, but it wasn’t until the Wild West shows of 1870 to 1920 that the cowgirl became a part of Western iconology.

The Wild West shows started as traveling vaudevillian performances that became open air events, showcasing romanticized notions of the American West. These included female riders in Western saddles and female versions of cowboy clothing, performing rope tricks and daring riding stunts that rivaled any of the male riders’ maneuvers.

Rodeos also became popular around this time, and women competed against each other and alongside men, even in the rough stock classes. But in 1929, when a female bronc rider was killed at the Pendleton Round-Up, women were banned from bronc riding.

Despite this setback, Hollywood loved the image of the cowgirl, and kept it alive in films. As early as 1912, cowgirls were appearing in silent movies, riding horses and keeping up with their cowboy counterparts.

Today’s Cowboys

Although the 1800s were the prime decades for the American cowboy, the independence, hardiness and freedom of spirit associated with this iconic character stayed alive in the mind of the public. The cowboy culture continued to live on, being preserved in Hollywood films, artwork, novels and even fashion. Today, the cowboy remains the ultimate symbol of the American West.

“The working cowboy of the mid-to-late 19th century came to embody the spirit and rugged determination characterized by the frontier life in many ways,” says Davis. “The American fascination with the Wild West and the mythic, gunslinging cowboy can be found everywhere, from television and movies to marketing and consumer goods. Just as the medieval knight or the Japanese Samurai represent iconic figures from their time and place, so does the American cowboy.”

Working cowboys still exist today in ranches throughout the West, where thousands of acres of land support what remains of the cattle industry. But these men (and women) represent only a small number of special people who have found a way to make a living doing what so many around the world have romanticized.

In fact, many modern cowboys retain their jobs by working at dude ranches, which are designed to give city dwellers a taste of the colorful cowboy lifestyle.

Source Material

For more info about the history of cowboys, check out the following resources:

◆ Brittanica.com

◆ Conquerors: The Roots of New World Horsemanship (by Deb Bennett, 1994, Amigo Publications)

◆ Cowgirl Hall of Fame

◆ Hollywood Hoofbeats (by Petrine Mitchum with Audrey Pavia, 2014, Companion House Books)

◆ NationalGeographic.com

◆ National Park Service

◆ Sid Richardson Museum

◆ Texas State History Museum

◆ “The Introduction of Cattle Into Colonial North America,” from Journal of Dairy Science, February 1942)

This article about the history of the cowboy appeared in the Winter 2024 issue of Western Life Today magazine. Click here to subscribe!